Stuart Moxham of Young Marble Giants: "It Was So Much About What We Didn't Want To Do"

- Joe Massaro

- May 28

- 9 min read

Few bands have left as lasting an impression with as little sound as Young Marble Giants. Formed in Cardiff, Wales in 1978, the trio of brothers Stuart (guitar, organ) and Philip (bass) Moxham and vocalist Alison Statton crafted music defined by its restraint: stark guitar lines, skeletal rhythms from a pre-set drum machine, and a voice so gentle it became its own form of intimacy. Their sole album Colossal Youth (1980) stood in sharp contrast to the noise and posturing of the punk and new wave scenes surrounding it, and yet it resonated with clarity, vulnerability, and a sense of space that felt radical in its own right — "young, gifted, marbled." Despite their brief lifespan, the group's legacy continues to ripple through generations of both pop and experimental artists. In the interview below, Stuart Moxham reflects with openness on the group's improbable formation, their aesthetic stubbornness, and how constraint and intuition shaped one of the most quietly influential records of the 20th century.

Hot Sounds: Given that your older brother Richard was bringing back far-out sounds from abroad, and you were absorbing progressive and folk records in solitude, what role did contrast or contradiction play in shaping your musical vision? Did part of you crave simplicity as a rebellion against complexity?

Stuart Moxham: I think it was the sheer variety that fed me musically. As long as it was all good stuff (and there was so much good stuff in my youth and teens) I guess it went in deep. Listening repeatedly, of course, imprints music into a person and listening on good enclosed headphones lends privacy and intimacy. Two perfect elements in consuming music. The simplicity of YMG music was mostly a rejection of the way that most music arrangements were/are a major contribution to the orthodoxy of so much popular music and I was convinced we were wasting our time as nobody we knew, even vaguely coming from Wales, had succeeded. We also found immediately that Phil and I, with the rhythm generator, worked really well. It didn't need anything else apart from Alison singing.

HS: When the three of you came together from the ashes of True Wheel to form Young Marble Giants, what were your first impressions of each other musically by '78? You and Philip, of course as brothers, had that "telepathic" musical bond, but how would you say Alison's presence contributed or changed the dynamic?

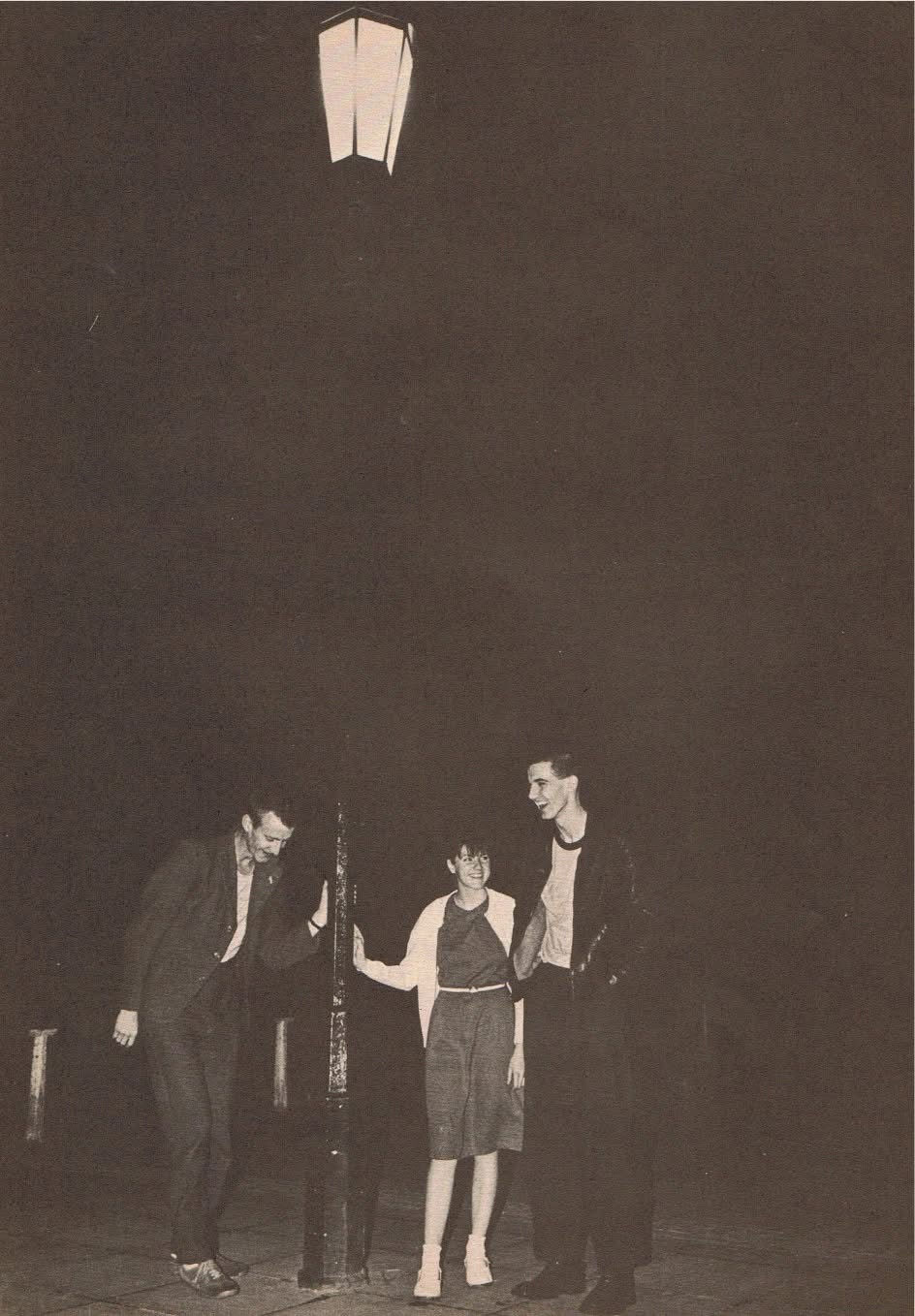

SM: Because True Wheel was a covers band largely (I think we did include a couple of Matthew Davis' own songs occasionally) musicianship, as such, was not really too critical. We were all at least adequate, I suppose. Alison was one of two female backing singers in that group, so somewhat secondary in the overall sound. She could definitely hold a tune! It's interesting; we three all had the (obvious) idea of forming our own band, after failing to find another one to join, and I certainly never thought about our individual capabilities. We were somewhat seasoned by then and it was much more a case of "concentration is controlled excitement" as our focus was on the nature of the material we were going to make. I was famously unhappy with having anyone else in the band — Alison just happened to be the unfortunate recipient of my resentment; it really wasn't personal. Consequently I didn't pay much attention to her contribution. I realized long afterwards that she was a super fast learner, getting my melodies spot on first and every time after and (it took decades for me to appreciate this) we have a similar vocal range: Alison could comfortably sing everything I could. Just as well, because I hadn't even heard of transposing and had never seen a capo! Over the decades of course I have come to see that her untrained voice was a radical and very enabling element. She was singing so sweetly about these sad and heavy subjects; as John Henderson of Tiny Global Productions once said to me, there was an incongruity to this bobby socked, wholesome girl mouthing lyrics which seemed far too worldly for her to have experienced. I take my hat off to her for many things, not least putting up gracefully with me and also going upfront onstage, every time, absolutely terrified.

HS: The passage you quoted on the Final Day EP sleeve about the "young marble giants" as incomplete fusions of geometry and vitality feels like more than just an evocative image. Did you see the band's sound as embodying that tension between abstraction and life? Were you, in a way, trying to carve emotion into something fixed and architectural?

SM: It was, as ever for me, the other way around. We made the music, and I chose the name and images for the EP sleeve, before realizing how pertinent those descriptive quotes were.

HS: The interplay between tape hiss, stillness, and voice on Colossal Youth is almost like a kind of domestic musique concrète. Have you ever thought about the record in that way? If not, how do you see it in retrospect?

SM: Hmm. I didn't consciously see that at the time. It's almost impossible to see one's creations as other people do. Everyone brings their own experience to art. That said, I can see that it has those elements, once someone describes it that way. In everything I ever produce; music, lyrics, poetry, prose, I have never set out to try to make something — it all comes from a tiny idea, or some unconscious muscle movement on an instrument, which excites me into unravelling....whatever it is. I don't know the notes on the guitar for example, without having to work them out, I work from the shapes of basic chords learnt by rote. My fascination with the guitar, in an ongoing self — taught way, has meant I am in a sort of evolutionary progress with playing and, because I am experimenting with the little I know, I stumble on things which inspire me. It's the opposite of learning everything formally, objectively, which for me (probably because I am deeply Aquarian) is anathema. It's all about the personal journey. Making art is going from the particular to the universal.

HS: What's the most misunderstood thing about Colossal Youth from your point of view, even now, 45 years later?

SM: Perhaps that it was conceived exactly as it exists. In our capitalist, consumer culture we get finished products. We rarely think about how they come to be; about all the time and effort, the experimenting etc. before the item is marketable. We simply take it as it comes, when actually it may have gone through many revisions etc. to get there. Phil and I barely discussed our criteria; probably one short conversation about minimalism and brooking no corny rockist shit. It was so much about what we didn't want to do, i.e. what everyone else does. It seems to me that popular music is a very conservative thing. I had spent time in Cardiff Art College, mostly in the library, and was very turned on by the Fine Art mindset. So I felt that there was a lot of stuff we could do that had never been done, in music, at least. But the actual making of our music was a process of tapping our innate family musicality and both keeping a weather eye on any tendency to stray from the largely unspoken mutual vision. If it sounded right it was right. We didn't struggle, it just came to us.

HS: How much did working with rudimentary recording equipment (the reel-to-reel, the organ's rhythm box) shape your sense of time and space in music? Do you still feel that imprint today?

SM: Recording was, for us, a simple need to hear what we were doing in our room; a way of getting some objectivity about the material, the performances, the sound balance between the instruments and vocals, etc. We only had a mono reel-to-reel, an old ribbon mic and an early mono cassette recorder, alongside our instruments and stage amps. Contrary to some reports, we had no synthesizers — it was the late '70s, after all, and such things were barely available, except to supergroups. To answer your question though, I guess the rhythm generator, being so unlike what any drummer would or could do, informed us a lot. I can't remember, but I imagine I wrote some of my guitar parts/songs to those crazeee beats!

HS: The Hurrah performance from 1980 has become a defining document of the group's live presence. Did the starkness of that setting, both visually and sonically, feel like an extension of your aesthetic, or did it challenge it in unexpected ways? What do you remember most from that performance?

SM: Oh dear. If you watch the video of those Hurrah gigs you will see three utterly miserable, isolated people. We even shortened the song arrangements, just to get off stage earlier. We weren't talking; Alison had been really ill, she and Phil had parted as a couple on that tour and we were all shell shocked by three sold out tours in seven months for a project I, certainly, had expected to fail. We had no manager, there was no tour management in those early Rough Trade days and as naive, sensitive types it was all far too much. Fame is a horrible, corrosive thing which very few people survive without scars. Of course there was more to it than that, we enjoyed a lot of it but we were completely unprepared for our success and the fallout still affects us personally to this day. Huge marijuana intake was our coping mechanism but also a real problem in hindsight.

HS: The G!st felt like an attempt to keep the emotional economy of YMG intact, but stretched into looser and more atmospheric terrain. Did that project feel like a continuation or a reaction after the intensity and finality of Colossal Youth?

SM: Looking back, The G!st began as the first fantasy record sleeve I ever made – during 1979, when we were writing the YMG material. I may have been hedging my bets in the likelihood of the band failing, by setting something else up, if in name only. Your assessment does suit the first singles and the album, but again, I was on automatic pilot — just doing whatever came into my head. What we would now call my mental health was a big mess — the frog's heart still beating after being removed from its body. To me, as someone almost completely numb, it was nothing conscious; neither a continuation nor a reaction to YMG. It was horrible to be that way and I really only felt shame about that early stuff for the longest time. I have only been able to see it at all subsequently because people have said what they feel about it. The G!st was in many ways the opposite of YMG, which was a supremely confident writing partnership and gigging band.

HS: The Words and Pictures zine feels like an intimate window into the world of Young Marble Giants, blending personal thoughts, art, and song lyrics in such a unique way. How did you approach creating the zine, and what was the intent behind using it as a medium to communicate with your audience at that time?

SM: It was inspired by seeing how other bands made merchandise, and by the friendliness of Better Badges, who were operating close to Rough Trade's shop in the Westway area, at the time. My then girlfriend Wendy [Smith] came on tour with us and was always sketching, so I combined her work with the lyrics, which weren't available anywhere else, and a couple of poems, to make the booklet.

HS: So many people discovering Young Marble Giants today weren't even born when the three of you were first playing together. What do you think it is about the group that continues to resonate across generations?

SM: I think that YMG's music was/is both shockingly skeletal but also full of ideas. I realized how sad many of the lyrics were when I first saw them all in one place for the Domino release — but there is also humor in the mix, something no-one has ever mentioned. Overall I also discovered, after our final reunion gig in 2015, that our music "operates on the level of the heart" according to Alison's husband. (I had asked him why our audiences overwhelmed us with love). I think we also partially succeeded — a million times further than my wildest hopes — because we did reject so much musical orthodoxy.

HS: I'm sure there are many, but is there a single moment, memory, or scene that, to you, captures the essence of Young Marble Giants?

SM: It's surprisingly difficult to think of one moment, element or scene which was quintessentially YMG. Perhaps we were defined by always being uncompromisingly YMG in our band togetherness. We were very pigheaded about things, e.g. having to be practically begged to contribute to the Cardiff compilation album Is The War Over? — which was what got us interest from Rough Trade. I think we had enormous confidence, very quietly. We knew that our music had quality, novelty and therefore power so there was a feeling of being above the musical conventions, (certainly of R'n'B Cardiff,) which only we experienced. Rejecting mainstream music and its conventions, like doing encores, (phony!) or staying in the dressing room and not hanging out in the venue before playing, came with the territory. Both those later quirks rapidly evaporated by the way — some things exist for good reasons, like theatricality and personal safety, for example.

Colossal Youth (40th Anniversary Edition) is out now on Domino.